Modules

Visualization

Reactions are visualized with the open-source library cytoscape.js (example of interactive version; more can be found under Experiments.)

Data Structure

The classes ChemData, ReactionRegistry and

all the various individual reaction classes (such as ReactionSynthesis or ReactionEnzyme)

store the data about all applicable reactions,

including stoichiometry, reaction rates, reaction orders, thermodynamic data, and macromolecule data.

They also provide methods to set and view those values.

Specialized knowledge is stored in classes such as ThermoDynamics.

Details in the Guide.

At a later date, graph databases (the foundation of our sister open-source project BrainAnnex.org) will be utilized. For now, a simpler in-memory data structure is being used.

Computations

For single-compartment reactions, the users generally interact with the methods of the classes

UniformCompartment.

Specialized support classes include ReactionKinetics, VariableTimeSteps,

and Numerical. Details in the Guide.

Classes dealing with the spatial element, namely BioSim1D, BioSim2D and BioSim3D, create ad-hoc compartments for the reactions

– typically (but not necessarily) corresponding to their bins.

General Background and Terminology : Reactions and Stoichiometry

Recommeded readings:

- KINETICS

- Intro - Reaction Kinetics, by Claire Vallance

- Solid foundational - "Fundamentals of Enzyme Kinetics", by Athel Cornish-Bowden, 4th Edition (2012)

- More advanced/thorough - "Analysis of Enzyme Reaction Kinetics", by F. Xavier Malcata

- THERMODYNAMICS

- Solid foundational - "Essential Classical Thermodynamics", by Ulf Gedde (2020)

- More advanced/thorough - "Chemical Kinetics, Stochastic Processes, and Irreversible Thermodynamics", by Moises Santillan (2014)

For an ongoing discussion about books (and links to them), see our blog entry

Terminology

Consider a generic chemical reaction such as:

\(\require{\mhchem} \ce{aA +bB <=>[k_F][k_R] cC + dD}\)

where A, B, C, D are chemical species, while a, b, c, d are integers (the stoichiometry coefficients.) kF and kR are, respectively, the forward and reverse rate constants, as detailed below.

A and B are generally referred as the reactants, while C and D are the products of the reaction. However, to be noted that the reaction goes in both directions at the same time – imagine two adjacent rooms, where some people go from one to the other, while others go in the opposite direction.

As customary, we'll use square brackets, as in \([A]\) , etc, to indicate the concentrations. Generally, those are functions of time, \([A](t)\) , but we'll often omit the \((t)\)

If the concentrations change with time, the reactants as well as the reaction products must change in lockstep to satisfy the stoichiometry (i.e. maintain the relative balances.)

A: 100 , B: 300 , C: 50 , D: 200

and the reaction is

2 A + 4 B <-> 3 C + 2 D (i.e. with coefficients a = 2, b = 4, c = 3, d = 2)The net effect will be:

ΔA = -2 ; ΔB = -4 ; ΔC = 3 ; ΔD = 2

This corresponds to "1 unit of reaction". A larger reaction could be double, triple, etc, the amounts – but they all need to change in lockstep:

\(- \Delta A/a = - \Delta B/b = \Delta C/c = \Delta D/d\)

The flip in the signs indicates that some chemicals are produced while others are consumed. In the forward reaction, A and B are consumed, while C and D are produced; in the reverse reaction, it's the other way 'round.

The ratio \(\Delta C/c\) (the concentration of a product that is formed in a unit of time, adjusted for its stoichiometry coefficient) is called reaction rate, also known as reaction velocity.

Switching from Discrete to Continuous

Upon shifting our attention to large numbers of molecules in a liquid solution, one typically starts using real number and concentrations; for example, at time t0, [A](t0) = 12.425 billion molecules per liter.

Using primes to indicate the time derivatives (i.e. instantaneous rate of change) of the Concentrations functions, and omitting the (t) parts, the above example generalizes to:

\(- \ {1 \over a} [A]' = - \ {1 \over b} [B]' = \ {1 \over c} [C]' = \ {1 \over d} [D]' \)

The expressions with the [A] and [B] concentrations indicate the rate of change of the reactants;

the expressions with the [C] and [D] concentrations indicate the rate of change of the reaction products.

Again, \( \ {1 \over c} [C]' \) is defined as the reaction rate.

Numerical Methods

Don't worry – Life123 hides the details "under the hood"! This section is for those interested in the numerical methods...

To solve the ordinary differential equations for the chemical reactions, as well as for reactions coupled to diffusion or to membrane crossing, the simple and intuitive forward Euler method is being used at present. Grids of variable spacing (for variable time resolution) are also implemented with various heuristics.

At a later date, this approach will be complemented by the use of open-source libraries for solving ode's and pde's by various methods, and in particular using "implicit" methods for dealing with stiff systems of differential equations. Stochastic methods will be consider for low-concentration scenarios, for example involving macromolecule binding.

Exact Solution of Some Elementary Reactions

An exact analytical solution is available in some scenarios; in the

module ReactionKinetics, you will find the functions

exact_advance_unimolecular_irreversible(), exact_advance_unimolecular_reversible(),

exact_advance_synthesis_irreversible(), exact_advance_synthesis_reversible() (some are being added, and the names

being changed, as part of the upcoming release "1.0.0rc7")

Here, we'll work out one of the simplest example – the unimolecular reversible reaction:

\(\require{\mhchem} \ce{A <=>[k_F][k_R] B}\)

We'll write the concentrations of the reactant A and the product B, as a function of time, as A(t) and B(t).

From the stochiometry, we can see that for every molecule consumed of A, one molecule of B is produced ‐ and vice versa. Therefore : A(t) + B(t) = TOT , for some constant TOT. That's equation 1, below.

If the reaction is elementary (occurring in a single step), or can modeled as such, the net rate of production of B is its production rate (which is proportional to the concentration of A and to the forward rate constant kF) , minus its consumption rate (i.e reverse reaction, which is proportional to the concentration of B and to the reverse rate constant kR). That goes into equation 2.

Finally, we need to specify some initial condition; for example that at time 0, the concentration of A is some value A0 . That gives us equation 3.

\(\begin{cases} & A(t) + B(t) = TOT && (1) \\ \\ & B\ '(t) = k_F \ A(t) - k_R \ B(t) && (2) \\ \\ & A(0) = A_0 && (3) \\ \end{cases}\)

Note that there's no need to specify an equation for the rate of change A'(t) , because it follows from (2) and (1) :

\( A\ '(t) = {d\over dt} A(t) = {d\over dt} [TOT- B(t)] = - B\ '(t) = k_R \ B(t) - k_F \ A(t) \)

As expected, A is produced from B based on the reverse rate constant kR, and is consumed based on the forward rate constant kF

Also note that at time t=0 :

\(A(0) + B(0) = TOT \quad , i.e. \quad A_0 + B_0 = TOT\) , where we're definining B0 = B(0)

The system of equations (1) thru (3) has the following exact, analytical solutions for A(t) and B(t) :

\(A(t) = [A_0 - {k_R \over k_F+k_R}TOT]\ \color{blue}{e^{-(k_F+k_R)t}} + {kR \over k_F+k_R} TOT\)

\(B(t) = [{k_R \over k_F+k_R}TOT - A_0 ]\ \color{blue}{e^{-(k_F+k_R)t}} + {kF \over k_F+k_R} TOT\)

we're emphasizing in blue the identical exponential part. Everything else is just constants.

Notice that at equilibrium, as t -> ∞ , the exponentials go to zero, and A(t) approaches kR * TOT /(kF + kR) , while B(t) approaches kF * TOT /(kF + kR). The ratio B(t)/A(t) at equilibrium is kF /kR , which is the reaction's equilibrium constant, as expected.

The above equations may be explored in Mathematica with:

B[t_] = ((kR TOT) / (kF + kR) - A0) Exp[-(kF + kR) t] + kF TOT / (kF + kR)

produces: TOT (satisfying equation 1)

produces: 0 (satisfying equation 2)

produces: A0 (satisfying equation 3)

Note that the system of equations (1) thru (3) may be solved symbolically in Mathematica with:

D[B[t], t] == kF A[t] - kR B[t],

A[0] == A0},

{A[t], B[t]},

t]

(with some algebraic rearranging, the answers given by Mathematica can be shown to be equivalent to the more concise form we gave above.)

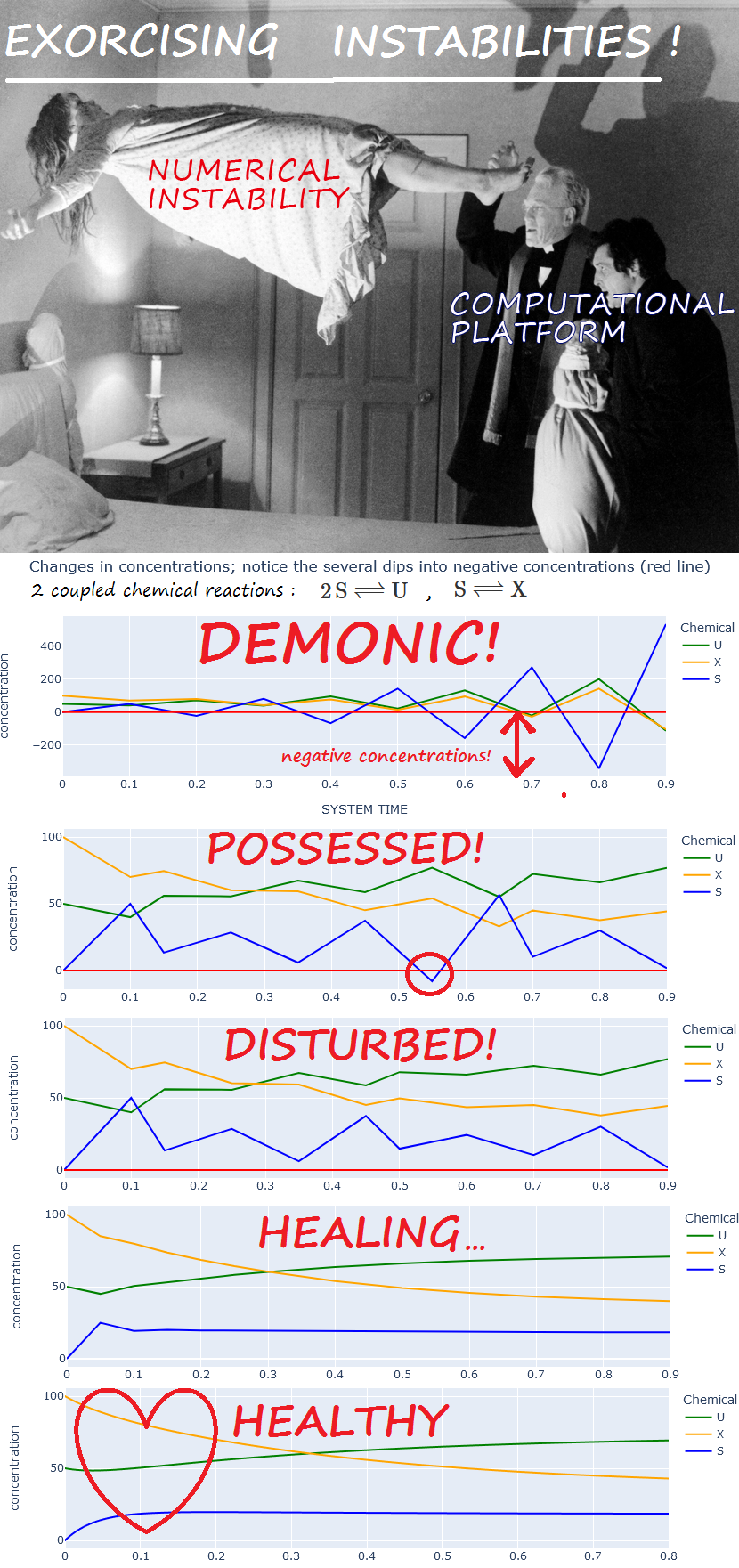

Numerical Instability

Numerical instability is a bane of solving ODE's! One advantage of dealing with variables that represent chemical concentrations, is that they must be always be non-negative. This constraint can be utilized to help detect instability: chemical concentrations assuming negative values may be used as an instability warning - not enough to catch all instances of instability, but helpful nonetheless.

3 scenarios may be distinguished. Illustrative examples are shown; "Delta_1" and "Delta_2" are the changes to the concentration of a particular chemical, arising, respectively, from two separate reactions.

| Description |

Initial conc. (of some chemical) |

Delta_1 (caused by reaction 1) | Delta_2 (caused by reaction 2) | Final conc. | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scenario 1 | A reaction causes a dip (of any chemical concentration) into the negative, and the combined other reactions fail to remedy it | 20 | -30 | +5 | -5 | |

| scenario 2 | A reaction causes a dip into the negative, and the combined other reactions counterbalance it enough to remedy it (return to positive) | 20 | -30 | +30 | 20 | though "counterbalanced", this is still regarded as a sign of numerical instability |

| scenario 3 | Scenario 3 : No single reaction causes any negative concentration, but - combined - they do | 20 | -15 | -15 | -10 |

Detection and Automated Correction of Some Instability

At present, Life123 uses negative concentrations, plus multiple heuristics, as a proxy for numerical instability. This appears to catch "the worst offenders", but not all cases, of instability.

Whenever an individual reaction - or group of reactions - causes any chemical concentration to go negative (under any of the 3 scenarios above),

a python exception of custom type ExcessiveTimeStep (defined in class ReactionDynamics) is raised.

That exception gets caught in the method ReactionDynamics.reaction_step_orchestrator() - which results in the following:

- the (partial) execution of the last step gets discarded

- the step size gets reduced by a given amount (which the user may modify)

- the run (simulation of reactions) automatically resumes from the previous time

The detection and automatic correction of negative concentration values is showcased in the experiment negative_concentrations_1

Macromolecules

Version Beta 28 introduced early initial support for macromolecules.

Occupancy of binding sites on a macromolecule, as a function of Ligand Concentration, can now be modeled.

(For example, Transcription Factors binding to DNA.)

Example:

In upcoming versions, the fractional occupancy values will regulate the rates of reactions catalyzed by the macromolecules...

Examples of usage may be found under Experiments (in the "Single-compartment Reactions" section.)